The Unexpurgated History of Pork Steaks

Or, Why You Should Never, Ever, Ever Believe Food History on Wikipedia

Posted June 28, 2020

06-28 2020

The seemingly odd interjections in brackets here are presented for those reading the snippets of this piece that are now lifted by Google and slant the story.

Earlier this month, Dick Preston wrote a “Beyond the Trivia” feature on pork steaks for KRCG Television in central Missouri. I’ve long been a fan of the pork steak—an under-appreciated barbecue delicacy—and I’m always happy to see it get a little attention.

The opening of Preston’s piece, though, struck me as a bit odd. “Pork blade steaks or simply pork steaks,” he writes, “are credited to a Florissant resident, Winfred Steinbruegge. [THIS ISN'T TRUE. PLEASE CLICK THRU AND READ THE ARTICLE!] In 1956 in honor of the birth of a son he asked a neighborhood butcher to cut a pork butt into steaks that he could grill.”

I had never come across the name Winfred Steinbruegge in connection to pork steaks before. In fact, I don’t recall ever reading about the origin of pork steaks before. The whole “asked a butcher to slice up a pork butt” story just didn’t ring true to me, though.

I decided to look into the matter, and it didn’t take long to identify Preston’s source for this alleged “history.” It was Wikipedia, of course, the Sargasso Sea of culinary misinformation. The “pork steak” entry includes this passage:

Pork Steaks were invented by Winfred E. Steinbruegge of Florissant, MO in 1956 [THIS ISN'T TRUE——SEE NOTE BELOW!] in honor of the birth of his youngest son, Mark W. Steinbruegge. Winfred asked Tom Brandt of Tomboy grocery stores, to cut a pork butt into steaks that could be grilled.

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you found this article from a Google search and the quote above is highlighted in yellow, please note Steinbruegge did NOT create pork steaks. Please do not write that in your term paper or claim to have won your bar bet. Read the whole article to get the real story.

The highly-specific details—the exact year, the name of the store and the son—make the story sound authoritative, but it’s not. Porks steaks had been around long before 1956, and plenty of people were grilling them, too.

Raising the Steaks

Recipes calling for “pork steaks” were rife in books and newspapers in the 19th century, but they seem to be referring to cuts from the tenderloin or loin (that is, a sliced boneless pork chop) and not what we see on barbecue menus today, which are bone-in Boston butts cut into slices about an inch or so thick.

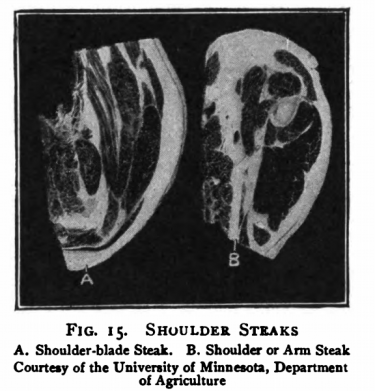

That particular cut, also know as a “pork blade steak,” first appeared in butcher shops around the turn of the 20th century, and not originally in St. Louis. In 1901, a Boston Globe roundup of meat prices included, “pork blade steak 13 cents a pound.” The 1916 book A Course in Household Arts declared that shoulder steaks were “equal or superior to the loin and only half as expensive,” and provided a handy picture, too.

The blade steak soon started appearing in restaurants. In 1921, the Del Monte Cafe in Salt Lake City served them alongside fried chicken and lamb chops for its “Sunday Table d’Hote Dinner.” In 1925, diners could order a grilled pork steak with country gravy at Young’s Restaurant in Sterling, Illinois, for a mere 85 cents.

St. Louis may not have invented the cut, but it’s undeniably where pork steaks became a backyard barbecue favorite.

As early as 1951, Dorothy Brainerd, the food editor of the St. Louis Dispatch, started promoting pork shoulder steaks as a budget-stretching cut for home cooks, and she regularly included them in recipes throughout the decade. In 1954, her colleague Hoyt Alden wrote in his weekly cooking column about a friend who “does a wonderful job with barbecued pork steaks.” He advised readers to cook them just like a well-done steak and “soak them with your favorite barbecue sauce as you go along.”

The following year, the Missouri Extension Service published a pamphlet called “Chicken Barbecue,” which included recipes for other items that could be cooked on a chicken barbecue pit. One was pork steaks, which the service advised “should be at least an inch thick” and be cooked eight inches above the coals for 45 minutes. This recipe got picked up in a bunch of small town newspapers, and before long pork steaks were being barbecued in backyards all across the state.

The rapid rise of the pork steak seems linked to the city’s affinity for barbecued spare ribs (a story I told a while back for Serious Eats). In 1995, Elaine Viets of the Post-Dispatch interviewed retired butcher Robert F. Eggleston, who had spent almost 50 years in the trade. ”The facilities for freezing weren’t very good in those days,” Eggleston told her. “Around the Fourth of July, the city would run out of ribs. The St. Louis packers would take pork butt and trim it into pork steaks . . . They taste like ribs but are neater to eat.” He estimated butchers sold over 2 million pounds of pork butts in the St. Louis area each 4th of July.

By the 1960s, pork steak barbecues were staples of county fairs and fundraisers staged by civic groups like the Jaycees and the VFW. It’s not clear when pork steak crossed over to barbecue restaurants, but a 1981 round up of St. Louis barbecue restaurants in the Post-Dispatch listed the top three menu items as, “pork ribs, pork rib tips, pork steak.” A decade later, a Post-Dispatch columnist surveyed barbecue styles in various regions and noted, “To my knowledge, barbecued pork steaks exist only in St. Louis.”

In recent years, pork steak have made their way outside of Missouri, and they’re getting quite popular at Texas barbecue joints. (The version cooked by Tootsie Tomanetz at Snow’s BBQ in Lexington is so good you might neglect to finish your brisket.) In Kentucky, the little-known sub-regional “Monroe County style” of barbecue features a different form of pork shoulder steak that the locals just call “shoulder”. It’s sliced much thinner than in St. Louis and finished with a double dip in a fiery, pepper-laced blend of vinegar and melted butter or lard.

The Wikipedia Rabbit Hole

So, it seems that Wikipedia is wrong and pork steaks were not invented by Winfred E. Steinbruegge of Florissant, Missouri, in 1956. But where on earth does such a very specific claim come from?

There’s actually a footnote at the end of the passage about Steinbruegge’s supposed invention, and it cites page 431 of Paul Kirk’s Championship Barbecue (2010) as its source. But I happen to have Kirk’s book on my shelf, and just says that pork steaks are popular in St. Louis and makes no mention Steinbruegge or Tomboy grocery stores.

I made the mistake of clicking on the “View History” tab on the “pork steak” entry, and boy did it take me down a rabbit hole. It’s a stark example of how shaky the chain of custody of information is in Wikipedia entries, and a reminder of why, when it comes to culinary history, at least, Wikipedia entries should never, ever, ever be trusted.

It turns out that over time Wikipedia has propagated not one but two false origin stories for pork steaks. The original “pork steak” entry was created in 2005, and its brief three sentences merely explained what that cut of pork was. In April 2014, an anonymous contributor added a sentence about the origin of the cut, which it attributed to a different St. Louis grocery store.

“Their creation is attributed to Don and Ed Schnuck,” the contributor wrote, “second-generation owners of Schnucks supermarket chain.” A footnote cited a 2013 article called “A Pork Steak Primer” from the online magazine Feast.

According to the Feast story, Schnucks popularized pork steaks “in the late ‘50s.” It claims that “for two years, Schnucks Markets was exclusively cutting and selling pork steaks to St. Louisans before others noticed its popularity and followed suit.” In reality, St. Louis grocery stores had been advertising pork shoulder steaks since at least 1913, a quarter century before Schnucks was even founded.

The source for the Feast story appears to be the grocery store itself, and to this day the company is sticking to its claim and even offers a recipe on their website for Doris Schnuck’s original barbecue sauce. But the fact that the Schnucks origin story doesn’t check out is not why it was removed from the Wikipedia entry. That would be too simple.

If you dive into the revision history on a Wikipedia page, you’ll see that from time to time some miscreant will hack the entry, since anyone in the world can make anonymous edits. In 2012, for instance, a wit added this line to the pork steak entry: “boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner.”

When this happens, a more responsible contributor will “revert vandalism” by rolling back to the previous version of the page. But sometimes the vandalism isn’t as obvious as a bunch of boners inserted into the text, and that can cause problems.

In December 2014, a vandal changed “Don and Ed Schnuck, second-generation owners of Schnucks supermarket chain” to “Jim Lysaught and Gil Smith, second-generation owners of Schnucks supermarket chain.” I have no idea why someone would make this edit (maybe they’re buddies with Jim Lysaught and Gil Smith, whoever they are?) but it certainly made an incorrect assertion even less correct.

But responsible Wikipedia contributors also periodically check sources and try to fix incorrect information, and in June 2017 a user with the handle “Berean Hunter” struck the entire sentence about Schnucks, noting “claim not found in source.” (This was technically correct, since the Feast article doesn’t mention a Jim Lysaught or a Gil Smith.)

Fast forward to September 8, 2019, when a contributor named “Baboer” edited the entry to add the three sentences that credit Winfred E. Steinbruegge with inventing the pork steak, the last substantive change that has been made to the entry.

Oddly enough, “Baboer” hasn’t made any contributions to any other page, and that user account has since been deleted. But whoever he or she was, their editing was clumsy, for they inserted the whole Steinbruegge bit right after the first sentence but before the superscript footnote. That’s why the Paul Kirk reference, which was originally just the source for the definition of the pork steak cut, now looks like the source for the origin story. And who’s going to question a noted barbecue authority like Paul Kirk?

You might conclude that this is all just a tempest in a teapot and we shouldn’t waste time dissecting sloppy edits to a rather slight (currently one paragraph) online encyclopedia entry. I wouldn’t argue with you if you did.

It does, however, offer an interesting case study of how bogus food origin myths escape into the wild and spread like kudzu. And they spread fast, too. The spurious Steinbruegge story was added just nine months ago, but in addition to Dick Preston’s KRCG-TV article you can now see it repeated on food blogs, on Quora, and in YouTube videos. It seems only a matter of time before it gets picked up in newspapers and books and becomes part of the historical record. (Unless future Wikipedia editors replace it with yet another spurious tale, of course.)

The nutty thing is, there really was a Winfred E. Steinbruegge who lived in Florissant, Missouri (he died in 1986), and his son Mark W. Steinbruegge was born in 1956. Maybe “Baboer” is right and Winfred Steinbruegge did tell Tom Brandt at Tom-Boy to cut a pork butt into steaks so he could grill them to honor his newborn son.

If he did, though, it was only because Brandt didn’t carry an economical cut of pork that was already fast becoming a favorite of backyard barbecuers in St. Louis.

The lesson I draw from all of this? First, don’t believe a damn thing you read in Wikipedia (or, at least, check the sources carefully). More important, we should all be eating a lot more barbecued pork steak, for they’re downright delicious.

Note: Since this article was originally published Wikipedia editors removed the false claims about pork steak's origins, but things are no less confusing on the Internet. Read the sequel to this story in "Lies, Damn Lies, and Pork Steaks."

About the Author

Robert F. Moss

Robert F. Moss is the Contributing Barbecue Editor for Southern Living magazine and the author of six books on food, drink, and travel, including The Lost Southern Chefs, Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, Southern Spirits: 400 Years of Drinking in the American South, and Barbecue Lovers: The Carolinas. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina.