The Sauce That Barbecue Lost

Long Before Mississippi's Tangy Orange Condiment, Comeback Sauce Was For Barbecue

Posted December 15, 2020

12-15 2020

Not too long ago, the Northeast MS Daily Journal published a column by restaurateur Robert St. John on comeback sauce, a once-obscure Mississippi condiment that is now becoming known outside the state. The piece tickled something in my brain, for I remembered during past research coming across occasional references to barbecue served with “comeback sauce” a century or more ago.

It certainly couldn’t be the same thing as Mississippi’s now-famous comeback sauce, though. St. John calls that version “the offspring of the incestuous marriage of Thousand Island dressing and remoulade sauce.” A Greek restaurant in Jackson called the Rotisserie is generally credited as the originator. Pale orange in color, it’s used as a salad dressing and also as a dip for crackers, fried pickles, and shrimp. It’s definitely not something you would pour atop a smoked pork sandwich or slather on a rack of ribs.

St. John’s piece prompted me to dig a bit more into those earlier mentions of “comeback sauce” at old barbecues. That preparation, it turns out, might well be America’s great lost barbecue sauce, one with close links to the Great Migration and the emergence of barbecue as a commercial product.

It first emerged in Kansas City but has roots in Tennessee. The first reference I can find to a sauce called “come back” (or “comeback” or “kum-back” or “kumbak”, as it’s sometimes spelled) appears in the Kansas City Star in 1906 in an announcement of the annual picnic of the Ancient and Honorable Order of the Sons and Daughters of the Kings and Queens of Jerusalem, a local African American organization. “The Rev. J. W. Hurse will cook the barbecue meats,” the notice reads, “with his come back sauce on the side.”

The Rev. Hurse served his sauce at many more Kansas City barbecues over the years. At the 1909 Emancipation Day celebration in Independence, the Topeka Plaindealer reported, Hurse was “in charge of Barbecue with his famous come back sauce.” Three years later, at the Emancipation Day celebration for Olathe and Johnson counties, the refreshments included “an old fashioned Southern barbecue, with Rev. Hurse’s comeback sauce.” (Note: this summer I explored the historic connection between barbecue and Emancipation Day celebrations in this piece on the Juneteenth holiday.)

James Wesley Hurse was an influential member of Kansas City’s African American community, notable for much more than his skills at the barbecue pit. Like Henry Perry, Kansas City’s pioneering barbecue restaurateur, he was a transplant from Tennessee, moving to Kansas City just before the turn of the 20th century as part of the first Great Migration of African Americans from the South.

Hurse grew up on a farm in Mason, Tennessee, and left home as a teenager to find work in Memphis. He moved to Kansas City at the age of 21, where he worked as a day laborer while earning a degree in divinity from the Washington School of Correspondence. In 1898 he began preaching under a tent in the northeast Kansas City neighborhood nicknamed “Hell’s Half Acre”, and he baptized converts in the Missouri River. Five years later he established St. Stephen Baptist Church, a congregation that is still active today. In addition to serving as the church’s pastor, Hurse operated a restaurant called the Baltimore Cafe, and he cooked the barbecue at numerous public events in the decades that followed.

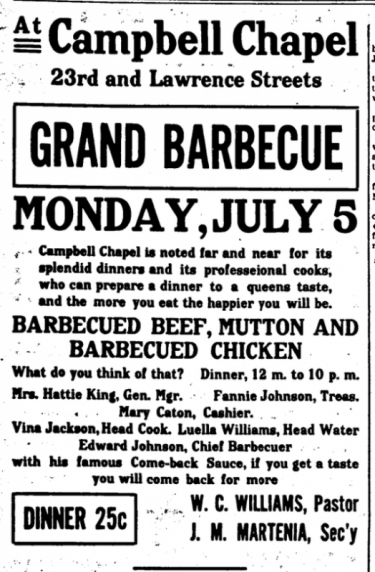

The Rev. Hurse may not have been the inventor of comeback sauce, for it pops up in other Midwestern and Western cities around the same time, always at African American barbecues prepared by transplants from the South. A 1909 advertisement in The Statesman for the Independence Day celebration in Denver, for instance, touted barbecued beef, mutton, and chicken, with Edward Johnson as the “Chief Barbecuer with his famous Come-back Sauce. If you get a taste you will come back for more.”

It was in Kansas City that the sauce took firmest root, though. It appears frequently in notices in the city’s African American newspapers, like the one for the Busy Bee Thanksgiving banquet in 1915, which highlighted “opossum, chicken, turkey, fish with dressing, and that come back sauce.” A picnic at Heathwood Park in 1916 featured baseball games, a fat man’s race, and “Old Time Barbecue and Come-back Sauce.” The term was so common in the community that it could be used metaphorically. A theater column in the Freeman, for instance, noted, “Mr. Walter L. Rector, producer, is a wonder. He always has a come-back sauce act for the public.”

As barbecue stands proliferated in the 1920s, come back sauce went commercial. It spread quickly beyond Kansas City and was touted on signs and in advertisements across Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, and Indiana. Though the barbecue was often described as “southern style”, the term come back sauce was found primarily in the Midwest—at least at first.

It was Midwesterners who ended up taking come back sauce back down South. In 1924, the Miami Herald reported that George Golding of Indianapolis, who was “generally known in his state the king of barbecues,” was building a barbecue stand called “the White Pig” outside of Miami, with meats cooked “rotisserie style, with the ‘original come back sauce.’” By 1928, the two Goody Goody Sandwiches stands in Tampa claimed to be “the only ones in town that can serve you the good old original ‘Come-Back’ Sauce.”

By this point, white diners were discovering come back sauce, and it enjoyed a brief period of vogue in the last half of the 1920s, which is when the first descriptions of the sauce’s ingredients and flavors appear. It certainly seems to have been quite spicy. When sharing a sausage recipe in her New York News column in 1926, Jane Eddington noted the seasonings "may seem mild to those who like the ‘come back’ sauce of this day, and more can be added.”

A more detailed description appeared the same year in the St. Louis Globe Democrat, which profiled the proprietor of a barbecue stand called Dad’s Place. When he first got started, J. S. Cowper told the newspaper, he hired as his cook “a real Southern Negro” who knew how to make come back sauce. “That’s brown sugar and cayenne pepper, mostly,” Cowper said. “You stew up a lot of bones and use the stock from them as the basis.”

Descriptions of comeback sauce in other places mention a meat stock base, too. In a 1928 article headlined, “Barbecue Sandwich Shops Spring Up Like Mushrooms,” the San Diego Evening Tribune noted the sandwiches were “seasoned with what is sometimes called a ‘come back’ sauce,” which it described as “meat juice with a good deal of water seasoned with a good deal of pepper, mustard, pickles and vinegar.” (The reporter, for the record, wasn’t a fan, saying the sauce was too thin and had “generally too much hot stuff.”)

The late 1920s seem to have been the peak of the barbecue version of comeback sauce. It kept appearing in advertisements for barbecue stands throughout the 1930s, and 1940s, but less and less frequently. The catchy name, though, was soon adopted and applied to other types of sauces, including the orange salad dressing that became such a sensation in Mississippi.

No one seems to have nailed down exactly when The Rotisserie added comeback sauce to its menu in Jackson, but recipes for it were published in various Mississippi newspapers starting in the 1950s. These call for a blend of mayo, ketchup, chili sauce, and Wesson oil that’s seasoned with onion, garlic, and red pepper or hot sauce. Over time it became, as Robert St. John puts it, “the queen mother of all condiments” in Mississippi. “We use it as an accompaniment to onion rings and fried dill pickles, and dress simple iceberg salads with it. . . I could make a meal out of saltine crackers dipped in comeback sauce.”

As a barbecue sauce, the spicy, stock-based comeback is now lost to the past. Kansas City's signature sauce today is a thick, sweet and tangy blend of tomato, molasses, and vinegar. But perhaps a few of the city’s pitmasters could start experimenting with a rich meat stock made from smoked bones and drippings, sweetening it with brown sugar and dosing it up with plenty of cayenne pepper. It just might be ready for a come back.

About the Author

Robert F. Moss

Robert F. Moss is the Contributing Barbecue Editor for Southern Living magazine and the author of six books on food, drink, and travel, including The Lost Southern Chefs, Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, Southern Spirits: 400 Years of Drinking in the American South, and Barbecue Lovers: The Carolinas. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina.