How Bourbon Really Got Its Name

Sometimes the Simplest Explanation is Right

Posted July 29, 2020

07-29 2020

The question of how Kentucky’s beloved aged corn whiskey came to be called “bourbon” has been the subject of much debate over the years. If you’ve read much at all about bourbon’s history, you’ve probably seen several contradictory explanations for the word’s origin. But there is one thing that whiskey writers all seem to agree on: bourbon whiskey was emphatically not named after Bourbon County, Kentucky.

That seemingly-plausible notion was gently dispelled a half-century ago by Gerald Carson in his 1963 book The Social History of Bourbon, the first serious history of the distilling industry in the United States. Carson attributes the confusion to the shifting geography of the Bluegrass State.

The land that became Kentucky was originally part of Virginia’s western Fincastle County. In 1776 it got carved off into Kentucky County, which in turn was divided into Jefferson, Lincoln and Fayette counties in 1780 and then into nine counties six years later, one of which was called Bourbon County. After Kentucky was admitted to the Union in 1792, the massive Bourbon County was subdivided several more times, ultimately creating 33 much smaller counties, one of which retained the name Bourbon, just to confuse whiskey buffs.

These repeated divisions have left historians flummoxed. There were scads of distilleries in the large territory covered by the original Bourbon County, but by the Civil War, when “bourbon” had become the standard term for Kentucky-made whiskey, only a few distilleries were operating in the actual Bourbon County. There were zero distilleries in Bourbon County from Prohibition until 2014, when craft distiller Hartfield & Co. opened its doors.

This paucity of actual Bourbon County distilleries has prompted commentators to seek other explanations. Gerald Carson kept it simple, speculating that people simply used “bourbon” to refer to the general region of northeastern Kentucky, not to the actual county. Chuck Cowdery, in Bourbon Straight (2004), elaborates on that theory. Noting that Kentucky whiskey was routinely advertised as “Old Bourbon whiskey” in early 19th century newspapers, Cowdery argues that “until about 1820 the entire region continued to be known popularly as ‘Old Bourbon’” and that the term was “simply identifying where the whiskey originated generally, i.e. somewhere in the region known as ‘Old Bourbon’.”

Both Cowdery and Henry G. Crowgey, author of Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking (1971) are adamant that the “old” part of “Old Bourbon” has nothing to do with the age of the whiskey being advertised. Crowgey declares that the term meant “unmistakably that the product originated in the region of ‘old Bourbon County’ rather than expressing a chronological factor in the quality of the goods.” The practice of aging whiskey in charred oak barrels, he notes, didn’t start until much later.

But that regional explanation hasn’t satisfied other writers, and they’ve stretched for more inventive origins. In Bourbon Empire (2015), Reid Mitenbuler notes that New Orleans was the biggest market for Kentucky whiskey and suggests, “a name like ‘bourbon’ would have been a perfect marketing tool, appealing to the city’s large French-speaking population.” Mike Veach takes this line of thinking a step further in Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: an American Heritage (2013), speculating that the name might have come from “river travelers drinking the aged whiskey of New Orleans on Bourbon Street and starting to ask for that ‘Bourbon Street whiskey.’”

These creative theories do get around the annoying fact that there weren’t many distilleries in the actual Bourbon County, but the documentary evidence tells a different and rather simpler story. I’m convinced that in the 1820s, at least, when people advertised “Bourbon whiskey” for sale, they were indeed talking about whiskey from a specific county in Kentucky. When they say “Old Bourbon” they absolutely were talking about the age of the whiskey itself, not a historical qualifier for the region.

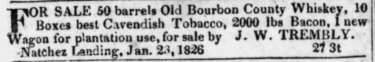

In August 1824, S. & H. P. Postlethwaite of Natchez advertised in the Mississippi State Gazette that they were offering for sale “100 Barrels Superior Bourbon County Whiskey” (emphasis mine.) In 1825, another Natchez newspaper, the Ariel, printed an ad for 200 barrels of superior “Bourbon county, Ky. Whiskey.” A year later, an ad in the same paper offered “50 Barrels Old Bourbon County Whiskey.”

It seems pretty clear that Bourbon whiskey really does get its name from the county in Kentucky, not from Bourbon Street or the old French monarchy. But which Bourbon County were those ads referring to, the original large Bourbon or the newer, smaller one? I think it was the latter.

In the two decades after the Louisiana Purchase, improved river traffic made New Orleans the primary market for flour, whiskey, and pork from Kentucky and the other new states along the Ohio River. In the mid-1820s, advertisements in the New Orleans papers announced the daily arrival of flatboats from various parts of the “western country”, including ones from “Bourbon County, Kentucky” that bore tobacco, bacon, and whiskey.

Yes, Bourbon County is well inland from the Ohio River, some 50 miles from what was then the primary Ohio River port of Maysville (known early on as Limestone). But it had water access to the Ohio via the South Fork of the Licking River, which was navigable by small boats and an important avenue of trade for the Kentucky interior. Its products were much in demand, too. An 1819 advertisement in the Baton-Rouge Gazette offered for sale flour “from Bourbon County, where the best wheat in the state of Kentucky is raised.”

Bourbon County’s whiskey seems to have been in demand, too. The advertisement cited above from S. & H. P. Postlethwaite of Natchez specifies that the “100 Barrels of Superior Bourbon County Whiskey” they are selling are “‘Spears’ and other brands”—one of the first instances of a distiller’s name being used as a brand.

The Spears in question is likely Solomon Spears, son of the early Kentucky distiller Jacob Spears and himself a noted whiskeymaker (“Spears” or “Speare’s Old Whiskey” appear in many of Lexington merchant David Bradford’s advertisements in the 1830s.) Spears’s farm and distillery were a few miles northwest of Paris in the actual Bourbon County.

In the early years, at least, when merchants advertised “Bourbon County whiskey” they probably really did mean the newer, small Bourbon County. Over time the “county” part began to be dropped, and the term “bourbon” was applied to Kentucky whiskey more generally and then to that particular style of corn whiskey, regardless of where it was made.

But what about the “old” part of “Old Bourbon Whiskey”? If people in the early 1800s called the entire northeastern part of Kentucky “Old Bourbon,” I’ve not found record of it. It’s true that distillers didn’t start aging corn whiskey in charred new oak barrels—the defining characteristic of bourbon today—until decades after it started being called bourbon. But consumers had long known that the more time spirits sat in the barrel the better they tasted, and “old whiskey” had been a term in the trade since the late 18th century. (“Old rum” had been used long before that.)

You can find the term “Old Whiskey” in thousands of advertisements in the early 19th century, and it’s frequently combined with a place name, like “Old Monongahela Whiskey” and “Old Susquehanna Whiskey”—two Pennsylvania river valleys known early on for the quality of their rye whiskey. How old “old” is isn’t exactly clear, but merchants sometimes advertised the age of their whiskey, and seeing three years or even older is not uncommon.

Bourbon, the evidence suggests, really did get its name from Bourbon County, Kentucky. When people asked for “old Bourbon whiskey”, they really did mean “old”—that is, whiskey that spent many months and potentially even years resting in an oak barrel, even if that barrel hadn’t been charred inside.

That whole charred barrel thing—there are a lot of fishy stories about that, too, but I’ll save them for another time.

About the Author

Robert F. Moss

Robert F. Moss is the Contributing Barbecue Editor for Southern Living magazine and the author of six books on food, drink, and travel, including The Lost Southern Chefs, Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, Southern Spirits: 400 Years of Drinking in the American South, and Barbecue Lovers: The Carolinas. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina.