The Origins of the Package Store

Not something to keep under wraps

Posted June 4, 2016

06-04 2016

And then there’s the term “package store,” which is used in various parts of the country, including the Carolinas and New England, where it is often shortened to the “Packy.” Where on earth did that term come from?

One common explanation you hear is that various states, not wanting their citizens to be seen carrying disreputable liquor bottles on the street, mandated that liquor stores sell all their goods in brown paper bags—that is, in packages. This derivation is based upon the method of historical research I like to call “just making stuff up,” for there are no state laws that require that. The real story is a little more interesting.

In Southern Spirits: 400 Years of Drinking in the American South, I tell the story of the South Carolina Dispensary, an early and unique experiment in state-controlled sales of alcoholic beverages. (You can read all about the Dispensary in this excerpt in the Columbia Free Times).Under the Dispensary system, only the state government could sell alcohol in South Carolina. A “dispenser” was established in the seat of each county, and each county dispenser purchased liquor from the central dispensary in Columbia. All the saloons, hotel bars, and retail liquor stores had to close their doors. The term “package store” has its roots back during that period.

One thing to note about the booze industry at this point: up until the 20th century, most breweries and distilleries did not sell their products in glass bottles but rather in kegs and barrels. Bottles and stoppers at this stage were still unreliable and tended to leak or break during shipping, so most retailers bought beer and whiskey in bulk and transferred it into bottles and other small containers for sale in their stores.

When the Dispensary law went into effect in 1893, the only entity in South Carolina that could legally purchase barrels of whiskey and package it in bottles for sale was the state government. Former liquor retailers and saloonkeepers tried every dodge they could think of to skirt the law, including filing repeated lawsuits and scrutinizing every possible loophole in the state and Federal code. One possibility they seized upon was a U. S. Supreme Court decision from seven years earlier.

In Leisy v. Hardin (1890), the court had held that no state could confiscate property that Congress recognized as being legally imported into that state. Gus Leisy & Co., an Illinois brewery, had shipped a load of beer in barrels and bottles to Keokuk, Iowa—a dry state—sealed with metallic IRS seals. After the city marshal seized the beer, Leisy sued to get their confiscated property back. Because Federal law at the time did not ban the importation of alcohol into a state, the Court ruled, as long as the beer was still in its “original package” it was legal and could not be confiscated.

Immediately following the Leisy ruling, a number of sharp operators in Iowa and Kansas (also a dry state) threw open what they called “original package stores”—selling beer or whiskey in the same bottles or packages in which they received them from out of state wholesalers. Congress swiftly shut that down with the Wilson Act, which specified that all alcohol transported across state lines “shall upon arrival in such State or Territory be subject to the operation and effect of the laws of such State or Territory enacted in the exercise of its police powers.”

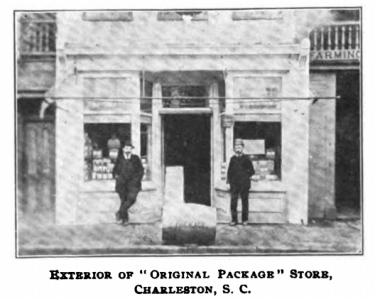

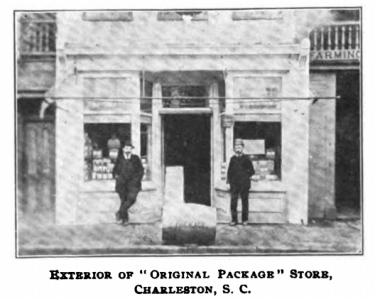

But, unlike Iowa and Kansas, South Carolina had not voted itself dry, so it wasn’t illegal for residents to buy and drink alcohol. The Dispensary opponents scored a big win in 1897 when a Federal judge ruled that, provided the booze was still in the same “original packages” in which it was delivered to the state, it could be sold directly to consumers. Within a month, the first “original package store” was opened in Charleston.

J. S. Pinkussohn, an agent for a New York wholesale firm, ordered 1,000 cases of liquor, which arrived via a Clyde Line steamer and was hauled through the streets from the port to Pinkussohn’s store at 269 King Street, observed closely but not interrupted by a party of state constables. Pinkussohn sold his liquor in gallon packages, but within days rival package stores opened their doors and started selling pint and half-pint bottles, too.

Original package stores soon spread to other parts of the state. In August, A. C. Linstedt opened a store in Orangeburg as an agent of Friedman, Keiler, and Co. of Paducah, Kentucky. Quart bottles were sold in “neat cedar boxes” while one- and two-gallon jugs were sold packaged in water buckets. A few weeks later, an entire carload of whiskey from S. Guckenheimer & Sons arrived in Columbia. Each bottle was enclosed in a pasteboard box, stamped and addressed to James Flannigan, the firm’s agent. If those smaller boxes had been shipped inside in a crate, that larger container would be considered the "original package," so instead they were packed loose in a box car filled with sawdust. Each bottle was enumerated on the bill of lading as being shipped to Flannigan.

The judge’s ruling was appealed, overturned, and reinstated several times in the years that followed, but the term “package store” stuck. The concept of selling liquor in the "original package" was incorporated into many states' laws after Prohibition to prevent retailers from buying bulk spirits and repackaging them, lest they water them down or adulterate them in some way.

The term is still used today to refer to liquor stores in certain parts of the country, and it tends to confuse people from other regions who aren’t familiar with it. And it has nothing to do with the brown paper bags that liquor bottles are wrapped in but rather the legal twists and dodges back in the strange days of the South Carolina Dispensary experiment.

Now, why is it that liquor stores in South Carolina display those three red dots on their signs? We’ll save that one for another post.

About the Author

Robert F. Moss

Robert F. Moss is the Contributing Barbecue Editor for Southern Living magazine, Restaurant Critic for the Post & Courier, and the author of numerous books on Southern food and drink, including The Lost Southern Chefs, Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, Southern Spirits: 400 Years of Drinking in the American South, and Barbecue Lovers: The Carolinas. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina.